Getting the “right” number of “good” invention disclosures

August 13, 2024 | 5 min readWe all know that building a robust patent portfolio starts with a healthy invention disclosure process. If inventors don’t disclose, you can’t protect.

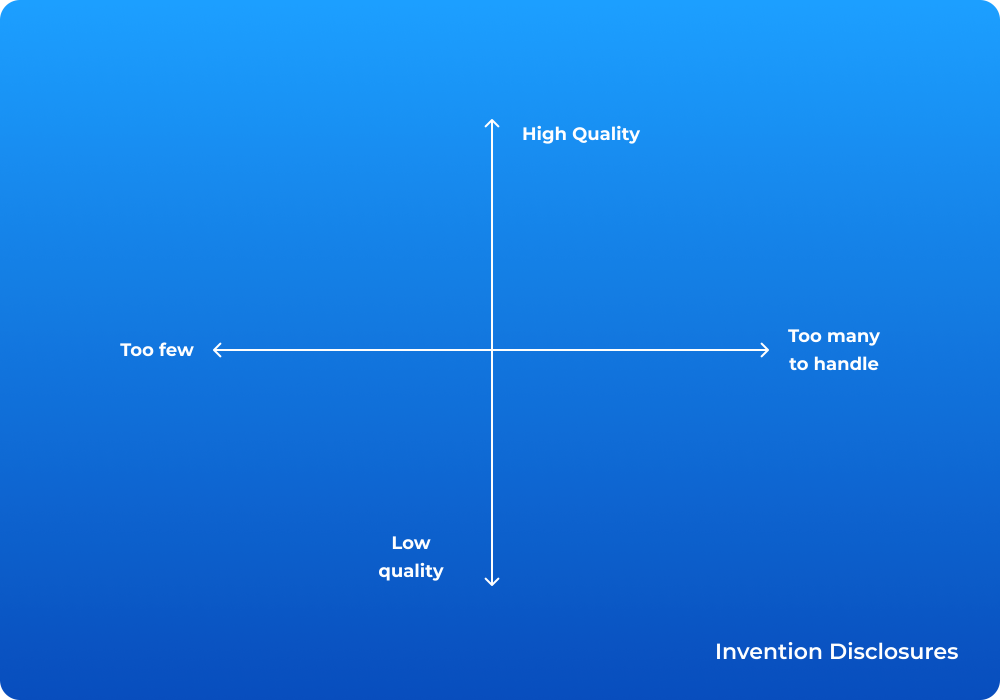

There are at least two dimensions to a “healthy” disclosure process: quantity and quality. IP teams should be conscious of their disclosures sweet spot, where the nature of their disclosure pipeline serves the organization best. This post will discuss the invention disclosure quantity-quality continuum that different companies sit on and offer tips on how they can steer the course. “We need more disclosures.” How many disclosures is “right”?

Many teams fall into the category of wanting more disclosures. But how do you know if this gap is within normal bounds or something to work on fixing? And how do you even know if you have a gap? How many disclosures should you be receiving?

Many companies like to benchmark themselves against their peers, but very little data exists regarding corporate disclosure volumes. Universities provide some insight. The Association of University Technology Managers (AUTM) surveys many universities annually, and the data suggests that universities receive, on average, about 3.16 disclosures for every $10m of research spending It’s hard to say whether 3.16 is a “good” volume of disclosures, but many universities we meet indicate they are trying to get significantly more than this number.

As you can see, there’s no exact science, but generally I would recommend looking at your high-performing industry peers to develop benchmarks of your own. Use your judgment, but disclosure volumes are likely to vary substantially industry by industry, so you might be well served to limit your research to near peers.

How do you do this benchmarking? Using back-of-the-napkin math, you can look at how many patents your competitors filed and how much they spent on R&D over the same period. Then, you have to make an assumption about their disclosure to filing ratio. Many companies file one patent application for every three invention disclosures they receive, so this is a reasonable starting rule of thumb. Using these proportions, you can estimate how many disclosures competitors received relative to their R&D budget based on both high, average, and low patent to disclosure assumptions. Then you have a benchmark to decide where you stand and what to do about it. Not perfect, but it’s a start.

What about too many disclosures?

Most IP teams would say they receive too few disclosures, but some companies receive too many. Let’s be clear: in an ideal world, no invention disclosure would ever be turned away (assuming it meets the minimum “quality” standards discussed below).

“Too many” often means that the IP team receives more disclosures than they can reasonably handle, but this can create unanticipated consequences. It creates pressure for IP teams, but more crucially, it can negatively impact inventors. Taking too long to process disclosures can send an inadvertent, discouraging message. Having a backlog erodes the credibility of the importance of disclosure, and burns up the goodwill of the inventors who do submit and then have to wait. Inventors are reluctant to engage with the IP process as it is, so more is not always more when it comes to invention disclosures, as is the case with many IP metrics when we peel back the curtain.

Defining disclosure quality

Disclosure “quality” is in the eye of the reviewer. From my experience, I define it as:

- Content: The disclosure contains enough information for the reviewer to understand the invention, including both the background problem that spurred the invention and the invention itself, with enough technical detail that a patent decision can occur with confidence.

- Clarity: The information is presented succinctly and the reader can get to the insights they need quickly. In practice, this means that the disclosure focuses on what is new or special about the invention rather than waxing poetic about the technology and field in a broad sense. Inventors love talking about their knowledge, and often struggle to define the boundary of background information versus new content. I can’t say how many times I’ve left an inventor interview having no idea about the right course of action.

Thinking about low vs. high quality

At the same time, remember that we can only ask so much of our inventors. Whether it’s their lack of interest or workloads that interfere, expecting high quality comes at a cost. Imagine that an inventor spends a day on making a disclosure clear and thorough. That wouldn’t serve the company’s goals, as they should be focused on their research. Or, think about the common scenario of invention disclosure requirements being so high that inventors don’t even bother. As I’ve written about before, most every IP organization would benefit from encouraging a “good enough” culture around disclosures to facilitate both their submission, and the opportunity for collaboration on less developed ideas. Like quantity, disclosures must be right-sized for the organization.

Putting it all together: The disclosure sweet spot for your organization

Improving the pipeline of invention disclosures isn’t one size fits all. Most organizations receive too few and low quality disclosures. If this describes your company, take heart in knowing you suffer a common problem. To fix it, I’d recommend first working on improving disclosure quality, the easier lift, and one that gives you more data for thinking about how to improve quality. Here, there are many techniques to consider, such as changing your invention disclosure form. Do you really need to ask so many questions upfront? Maybe it’s better to have the inventor share a basic overview of their invention, and to later, once you’ve qualified the idea, ask patent bar and other important questions. WIth a reduced initial burden, inventors may be more inclined to give you better content.

If you’re in the upper left or lower right quadrants of our completed graphic below, you’ve been doing something right. If you receive too few high quality disclosures, you’ve trained your inventors well. Help them understand that you’d rather hear about inventions imperfectly rather than not because inventors didn’t feel ready. If you receive too many low quality disclosures, it’s great that your inventors are in the habit of disclosing. Work with them to improve their disclosures, positioning it as a strategy for winning more patents.

This model of the optimal balance of invention disclosures is at this point only an emerging idea. It might very well be the case that it’s unrealistic, or that the true axes are different, or even that there’s more of them. Speed is a possible additional spectrum. Perhaps an organization doesn’t receive many disclosures, but is for some reason still slow to evaluate them. This scenario would come with its own set of factors, drawbacks, and solutions. If you have thoughts to add on this topic, I’d welcome them.

Balancing the quantity and quality of invention disclosures is essential for maintaining a healthy IP pipeline. While we usually want more disclosures, ensuring that they’re quality, thorough, and clear — and that your team can keep up — is equally important. Each organization has a goldilocks zone where disclosure quantity and quality align with their goals. Benchmarking against industry peers and encouraging a “good enough” culture of disclosures can help IP teams move closer to receiving the number of disclosures they need.